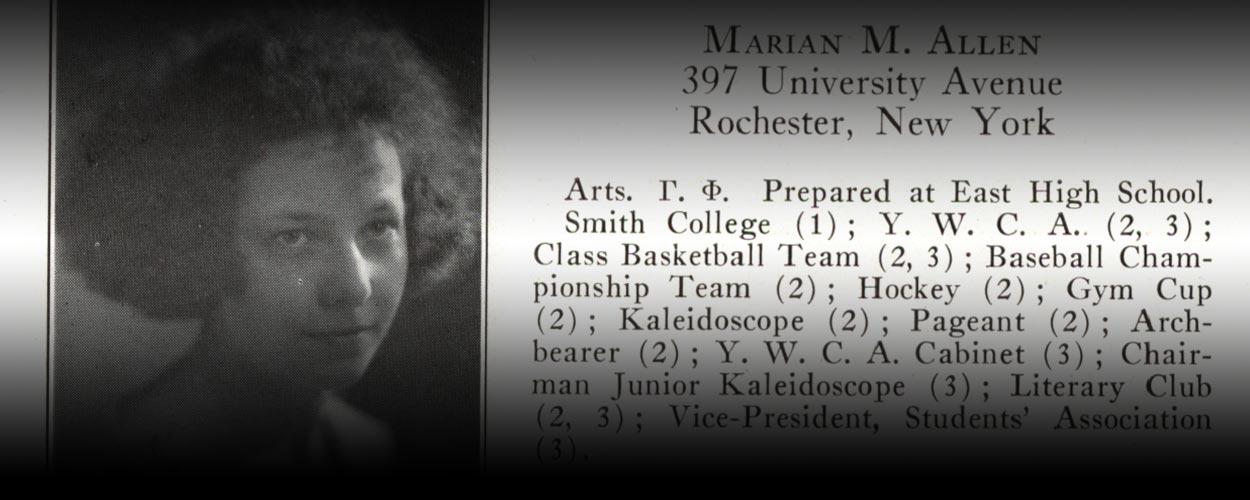

Marian Allen

Marian Allen

Marian Allen [1904-1993] was a member of the University’s Class of 1925. She entered the University in the fall of 1922, having attended Smith College for her freshman year. She received her MLS degree from Columbia University in 1934. Her career at the University spanned 42 years, most of those years spent in the Sibley Library on the Prince Street campus, and when that closed in 1955, the Rush Rhees Library on the River Campus. When she retired in 1969, she was the Head of the Reference Department. She was also active in the Memorial Art Gallery, the Civic Music Association, Rochester Association for the United Nations, the League of Women Voters, the American Association for University Women and much else.

Please note:

The views expressed in the recordings and transcripts on this website are those of the speakers, and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, the University of Rochester.

All rights reserved. Copyright 2019.

Helen Bergeson:This is a tape recording for the Friends of the University Libraries and I am visiting in the home of Marian Allen,[1] who was a member of the Class of 1925, and this is Thursday, August 12th, and this is Helen Ancona Bergeson.

MA: 1976.

HB: Yes.

MA: Bicentennial.

HB: We're going to talk about a committee that Marian was a member of, and the work they did in pursuing the history of the contributions people had made to the education of men and women at the University.[2] And hopefully we're going to start out talking about who was on the committee, and when did you meet, Marian, and what kinds of things were your business meetings concerned with?

MA: Yes, I think that's very important. We began - it was a committee that was appointed by President de Kiewiet. He was and is essentially an historian, and that was what was needed at that point in the University.[3] We were very fortunate to have an historian as the administrative officer at this point, because it had been accepted - the merger idea had been accepted. So that his - President de Kiewiet's idea was to appoint, and he did, a committee which he called the Sites and Traditions Committee which would look back over the past and evaluate the things in the past, clarify the things that should be carried on and preserved into the future, and take as many of the physical evidences of those traditions to the River Campus as were possible. And so we had a very wide view--anything that would - would preserve the past, and there was a long tradition because the Prince Street Campus was taken over by the College for Men of the University of Rochester, which was only men in 1853.[4] They had spent two years at the United States Hotel on Main Street.[5] In 1853 they came to the Prince Street Campus, given by Azariah Boody.[6] And the first building was Anderson Hall. So that we went over all of that history and looked at the buildings. I made a record - I was the Secretary of the Committee and I made a record of all of the inscriptions on and in the buildings for the record so that those records would be preserved. And I think it would be good to say that the minutes of all of these meetings are in the archives of Rush Rhees Library. Dr. de Kiewiet asked to have a copy sent to him, and a copy placed in the archives, so that any information that we got that appeared in the minutes can be consulted if anyone wants to look any particular things up. They - you asked who the committee consisted of. Carl Hersey, Professor of Fine Arts was the Chairman, and he was an excellent Chairman. He was - he moved things along, he kept things in focus, and he had a wide view of things. It was a very harmonious committee all the way round. And Dr. Slater, who for many years had been Head of the English Department, and had been retired for several years, was a major member of the Committee, very constructive and, of course, had great memories of things of the past. Gertrude Herdle Moore was on the Committee representing the Gallery. Charles Riker from the English Department of the Eastman School of Music, and Gilbert Forbes, M.D., from the Medical School. Charles F. Hutchison was on the Committee as a member of the Trustees, and I was on - I was the librarian of the College for Women, and I was the Secretary.

I do hope I don't forget to tell a little thing about Charles Hutchison later at the appropriate time because he was a choice person. He was very quiet, very warmhearted, very supportive, interested. He wasn't there as a Trustee who was bored to death by coming to a meeting that he felt was his duty. In fact, the whole committee came regularly. It had a wonderful attendance record.

HB: How often did you meet?

MA: Well, we met for almost two years before the merger, and the merger was in 1950,[7] I think. So that you see President de Kiewiet anticipated this--this was giving the committee enough time to get things in hand. And the year before we met, we would meet weekly, really weekly, and with good attendance. And Dr. Hersey would - we would have luncheon meetings in Cutler Union very often. Very often we would meet on the River Campus. We would meet wherever the major interest would be. But for the surveying the history, we would meet in Cutler Union--it was convenient for everybody. And we'd have luncheon meetings and then go on and on. And there was - it was nothing impromptu--there was no question that was brought up that was settled offhand. Everything was given solid research and due attention, and then brought up at a second meeting, and some of the names of buildings were just a continuing problem so that there wasn't a snap judgment. This Committee gave no snap judgments when they made a decision. It was a fascinating committee to be on really. There were also student representatives from time to time. But they really did not form a major part of - you see they did not have long - but their point of view was considered, and I think that's interesting to note, because this was 19 -

HB: It is. They didn't have much time.

MA: Right.

HB: This was a real broad horizon. Did you - did the business of this committee fall in convenient packages or compartments?

MA: Well, yes, I think they fell into things that had to be done. And the things that had to be done first - the first group of things that had to be done was to make a record of what was there. And then to decide how much that was on the Prince Street Campus could be transferred - both ideas and physical objects - to the River Campus. So, as I said the - I had never really been aware of inscriptions on buildings and within the buildings too much before I went around to each building and made that record. And it's important because- the University, you see, had had this long history, back to 1853,[8] and it represented a very honorable and admirable time in the history of the University.

HB: Now, you've pinpointed the birth of the Campus in 1853 when the men came from the United States Hotel. They were there by themselves up until 1900 when women were admitted. Now is there another pin - can you fill us in on some dates?

MA: What happened then? Well, the women, as you say, were admitted and there were just a few individuals admitted and allowed to go to classes in the beginning, and then the classes increased a bit in size. I was the Class of 1925, and we were just women attending the University there. I know as a senior - I happened to be the student president and I felt the responsibility of the women. And one thing that came to my attention was in thinking of Commencement, in our rehearsals, the Men's College went first. They didn't – they weren’t technically a College for Men and a College for Women until 1950.[9] But the unit of men went first in procession. And Dr. Fauver was the marshal, and he was such a lovable person, that I asked for an interview and I said, "Dr. Fauver, is this really necessary - do the women always have to trail the men? What is the reason?" And he said, "The reason is a very substantial one, logical. The men were here first and in the academic world things go by the date in which things occurred. In any inauguration of a new president you see the chiefs of the institutions that are re presented, who come as guests march in the procession in the order in which those institutions were established. So the age in which things occurred is important in the academic world." So that we all - all the gals relaxed, and we marched behind the men - so we had a good reason.

HB: Now tell me about one thing that -

MA: But the College - just to finish up - the College for Women as such as organized in 1930 -

HB: When Helen Bragdon came.

MA: When the men had moved to the River Campus, and Helen Bragdon came as the first Dean of the College for Women.[10] You see Dean Munro was Dean of Women.[11] There is that distinction. That's a real distinction. Dean Munro had been given the title Dean of Women but there was never a Dean of the College for Women until 1930 when the men moved to the new River Campus. And then the College for Men was there and the College for Women -

HB: Was on the Prince Street Campus.

MA: Right.

HB: Now what is the date of the actual merger?

MA: The actual merger was 1950.

HB: 1950. A hundred years after the inception -

MA: Almost. Yes, it was a hundred years. And it was almost a hundred years on the Prince Street Campus. You see, 1853. It was very close to the time when - they had been very nearly a hundred years there. [12]

HB: This was fantastic. What a delicious task you had!

MA: Well, such a thing as - a little thing comes up to my mind now. Even that black iron fence around the Campus - around the Prince Street Campus was important and valuable, and we had to find out whether or not any part of it could be taken to the River Campus and used in any connection. And the final decision - it was checked with people who know iron and know, you know, what can happen - was that it would not stand the move--it would disintegrate. A similar thing disintegrating was the statues in the niches of Sibley Hall. They were - here's another - here's a little story about Mr. Sibley, Hiram Sibley, who gave Sibley Hall. That was the second building to be built on the Prince Street Campus.[13] And he was so interested in having a fine building, a stable building, that he instructed the builders to build one story at a time. The basement was built one year, the next year the first story was constructed, and the following year, and so on. Well, he had been visiting in Italy and purchased for the niches in Sibley Hall some Italian statues. And they came over by freight, and were put on canal boats to send them along up to Rochester. And one rolled off, and they never could get it again. So that there was one niche that was never filled.

HB: Oh, which was that? Where was it located, do you recall?

MA: No, I think it was around the - I can't remember - either the East side or the West side. I'm not sure, isn't that interesting?

HB: Are they still there now?

MA: No, Sibley's gone.[14]

HB: Gone, yes. Isn't that fascinating? Where did it drop off, in the -

MA: I think in the New York Harbor when they were transferring it, you see…

HB: How about that!

MA: Never recovered.

HB: Fascinating story. Where did you learn it?

MA: Oh, I don't know. It just came over a period of time. And - and, you see, the question was whether or not those statues could be taken and used anywhere on the River Campus. And the answer there again was no. They were sandstone, and to be wrapped and lifted and transferred would really spoil them. They could not stand it.

HB: I see. What happened to them? Did they just go with the building?

MA: I - I was trying to think the other day. There is some vague story that is too vague. I’d hate to put it into the record. Someone who wanted them I think got them, but I'm not sure where they are now.[15]

HB: Interesting.

MA: But our sphinxes there on that same building, you see, and the question there was dear Mrs. Harper Sibley, who was such a good friend to the University and whose home was on East Avenue,[16] asked very tentatively if the Committee were planning to use - take the sphinxes to the River Campus, and if the Committee was not, she would like to place them in front of her home on East Avenue. But the decision there was that the sphinxes were very important to take to the River Campus, and they did. They went to the River Campus, and she accepted it.

HA: Where are they placed?

MA: Well, they were placed - there is a meridian - there are - there is a line from Rush Rhees Library to the River Campus, the Wilson Boulevard, and at right angles there - in that center where the Eastman Memorial is now - at right angles there is a line that goes right through between Morey Hall and Lattimore down to the lower quadrangle, and that line carries through between the two men's dormitories that were up at that time, Crosby and Burton, and the entrance to the steps leading into those two, Lattimore and Morey Halls, are now guarded by the sphinxes, right there. And President Anderson's statue follows that line and it is placed in the space between Burton and Crosby Halls. So that the statue of President Anderson - this we felt was very important -and we were pleased with the place that - where he was placed. Because, he really commands the lower quadrangle. Things would have been crowded on the upper quadrangle.

HB: Yes, yes. That's a good spot for that.

MA: So that's the story of some of the physical things. There were various plaques that were important. There was a plaque for the Medical School, that the Medical Library was being improved and enlarged, and a new plaque for that. Plaques, in other words, were another order of business for this Committee. The artistic - the material and the arrangement, the whole thing was - was brought up. Special committees - special sub-committees would be appointed for these things but they would report back to this committee, and get the reaction and suggestions. And then also there were - there was another plaque in the lobby of the - the big waiting room in Strong Hospital - for the purpose of that. So that we did quite a little on plaques. Then another physical detail was commissioned by the Committee. We felt that on the River Campus a dandelion should be, an impressive dandelion, a dandelion that could be seen at a distance. And so that was commissioned and I think William Ehrlich[17] did it. That's my memory, and I'm quite sure that's right. And it is a

beautiful dandelion, and that took time. You see some of these things stretched over a year or so. But the next question of interest was where it would be visible and people could see it who should see it, who would like to see it, and a final decision of that - you see, we would meet on the River Campus - we'd walk around the River Campus and look at things, you see, for the place for the president’s statue, all these things, we took nothing for granted--we really followed it through. So the final disposition of the dandelion was over the entrance of the Men's Gymnasium. And when I was on the River Campus recently for Dean Merrill's[18] luncheon, we looked out and I said, "I wonder if the dandelion can be seen from this new Wilson Commons." And it can be, so the dandelion is there, and it's loved, I hope.[19]

The other thing that was made that I think is probably the greatest thing that this Committee did was the Eastman Memorial, which is, as I suggested a minute ago, right in the center of the Campus. And this was the brainchild, to a great degree, of Dr. Slater. He phoned - he got some scientist to find out the exact latitude and longitude, and that is part of the record. There is a stainless steel circle on top of this round red marble piece, and that has the meridian, the latitude and longitude for the University of Rochester, and that, in that respect, is the heart of the University of Rochester. Its latitude is 43 degrees, 7 minutes, and 40 seconds north, 77 degrees, 37 minutes, and 49 seconds west, so if anyone wants to know where the heart of the University of Rochester is, in the Universe, there is where it is. And then he added two other things that I think are profound in a University. In words around the circle he gives a quotation - there is a quotation which he brought to the committee: “There is in wise men a power beyond the stars.”[20] And in our planetary probing of the present age, I think that’s interesting. And then in the very center of it has the formula for energy: e=mc2. So there you see you have the blend of philosophy and science that is a fundamental thing in any University. And then around the rim of the memorial there’s a black marble rim and the words: “Commemorating George Eastman’s gift for education, health, and music.”

HB: Oh, great.

MA: So that is a choice thing – that is really a choice thing - it’s a profound thing. And it gives unity to the University that is inescapable. And it is a thoughtful thing if anyone stops to think.

HB: Isn’t that delightful.

MA: (inaudible) a tremendous contribution to the University and this really was Dr. Slater’s, with lots of backing. Everybody was so pleased.

HB: I think it’s great.

MA: Now I would like to put in a little touch here about Mr. Hutchison. He was so informal--he was Charlie Hutchison to so many--he never was - stood on his dignity--he was so appreciative, so modest. And everything that people did he would - he would tell them how much he appreciated it. That memorial cost several thousand dollars - I think it was at least $10,000 - I don’t really remember - but it was not inexpensive. And when it was given and dedicated to the University, it was said, “Given anonymously.” And just recently with the well of stories about Mr. Hutchison’s death the statement was made that he had made the gift for the Eastman Memorial. And I’m so happy that he did.

HB: Think of the pleasure he got out of seeing that idea -

MA: There was no - that’s right, that’s right.

HB: Isn’t that grand.

MA: And he had the association with Eastman[21] that was so fine that the whole thing is what you hope can happen in an institution. And it did happen.

HB: Isn’t that great. To think of his seeing that conceived and worked on, and to be part of making it possible.

MA: He did. It’s really true, isn’t it?

HB: I’m glad you mentioned Mr. Hutchison because I’ve heard so many wonderful things about him. Helen Brandon referred to him as being the member from the Board of Trustees who was sent to her committee for the College for Women and how faithful he was -[22]

MA: He was always ready. That’s it.

HB: And he was so interested and supportive in everything they wanted to do. He never took anything but the most serious attitude about the business of that committee. And she spoke very highly of him. Isn’t that great. (At this point Miss Allen and Mrs. Bergeson are speaking at the same time and it is impossible to follow the conversation) - a little bit more about Mr. Hutchison.

MA: Institutions can be so impersonal. And things have to be done on a large scale so often that it is wonderful to know that the other kind can happen too.

HB: Oh, that's grand. I'm glad you thought of it, Marian. Now this is the memorial that is the center, the core, of the University?

MA: Yes, it's in the upper quadrangle.

HB: Is there a sundial there?

HB: No, there's no sundial. We also thought of taking up the sundial that had been in front of Sibley Hall, but children would break off the marker so often that we just finally decided it wouldn't be practical. But there is a circle of - there is a concrete circle - a seating circle - around this memorial, and in that there is a little plaque presented by the Class of 1932. And it's a great place to sit down with someone and have a conversation and look off toward the River or look off toward any of the academic buildings. You are in the heart of the University, and you have a rather comfortable wide cement place to sit.

HB: Isn't that grand.

MA: One more thing - physical thing - that we took up were the class tree markers. Now, that's in the 1800s the elms were planted that came down in a row - in a double row - from Anderson Hall, went around the circle and then followed out to University Avenue. And no doubt those classes were very aware of these young trees growing up, and felt happy about their being there. And many of them had a class marker. I can - in the 1860s - I remember several of them were in the 1860s. So that we didn't know really what to do with those. And this was not a perfect solution but they were taken up and put up on the upper quadrangle, scattered about among the elm trees that were there. When I went over the other day to look - as you know there are only two elm trees left, the two nearest the University Rush Rhees Library - and those old tree markers are no longer there. I hope they are preserved somewhere in the archives.[23] And the oak trees that are now planted have new class markers. And it amused me because the first one that I looked at said, "Dedicated to the memory of the deceased members of 1941," which seemed pretty solemn. And that idea was carried forth by 1943, 1945, and one said, "Deceased members - the deceased men of 1946.” But there's another- there's another stone that pleased me. It said, "Dedicated by the Men and Women of the Class of 1942."

HB: Wasn't that great.

MA: So that meant a very good trend--they finally got the point that the women - the men and the women could do something together and you did not have to be deceased to be honored. I like that. So the tree markers are going on.

HB: Marian, can I interject a question for just a moment? Was anything discussed about the Shakespeare oak?

MA: Yes, we did discuss that.

HB: What was their deliberation about that?

MA: Well, of course, there was really no way to transfer the Shakespeare oak. But there was a marking - (both women speak at once but HB wonders if it could have been grafted)- It didn't seem to - nobody picked it up - I don't know whether it was possible or not but nobody picked it up and did anything about it.

HB: Is it still over there at Prince Street or did it come down?

MA: I think it's now down. The plaque for the tree was taken up.[24] But that is a thing that we did not carry through on. I don't - it might have been possible. We did - there were several trees planted which are now no longer on the River Campus because the ground has been eaten up by new buildings. So that an effort was made from time to time to have memorial trees. I was glad to see that the tree that was planted for Donald Bean Gilchrist, who was the Librarian of the University, and who worked so hard to make the plans and carry them out for the Rush Rhees Library, and who died at age 50 after he had been in the Rush Rhees Library only a few years[25] - the tree to his memory that was planted very soon is still there up on the slope just to the north of the Library, and is in good shape. But the other memorial trees to individuals are no longer there. This is progress, I suppose.

HB: Now, what -

MA: Perhaps one other thing that we might - the major thing, after these physical objects were taken care of - the duty of the Committee was the naming of buildings. And this spread over several years. And in fact, I think President Wallis[26] - I know he carried on the Committee for a while on an occasional basis because he asked me to come to a meeting when they were trying to decide names for a small unit of dormitories. And that brings up the question that we - we felt in the naming of buildings - well, first, we were controlled by a long standing policy of the University that a building should not be named for a living person. This did two things: it relieved people of embarrassment who felt that they might have their names given to a building who were not - it relieved the University of embarrassment, you see. It was a clear-cut policy and it was a good one from that point of view. And also it gave a longer view to the place in the University that an individual took, really. So that, accepting that regulation, that only living - that only the people who were no longer living - names could be given to buildings, we worked - although we got names for some of the men's dormitories, the major thing was the Women's Residence Hall which was - the four halls that were in the formation of a cross on the hill behind the Rush Rhees Library. And we spent weeks and weeks and weeks, going over the history of the people who had contributed to the University. And Dr. Carl Hersey would stand at the blackboard - he was a Chairman who worked with a blackboard so that we knew what the agenda was, what we had covered at the last meeting, what we had not finished, what we were to pick up and carry on. He clarified things; he was a good organizer; he was a good administrator. And so it was months really that we were gathering ideas for names for the four halls of the Women's Residence. An almost automatic name that came up first was Dean Munro. Dean Munro had been given - her name had been given to the women's dormitory on Prince Street - very attractive dormitory - and I didn't blurt out at the beginning, but over a period of time, suggested that perhaps that was a recognition of hers that was deserved and was fine, but I felt that her contribution to the University was not so great that her name should be carried to the River Campus and perpetuated there. I was under her jurisdiction, being a member of the Class of 1925, and over a period of time, I have felt that members of the women's classes in the middle category - her friends were - her classmate at Wells was - Wellesley - was Mrs. William B. Hale[27] - and she was very responsive to the trustees and the friends of the Hales. She was very responsive to the people at the other range of life, and encouraged students who had no money at all, but she really was more of a preceptress than a Dean of Women. In fact, although she had the phrase Dean, the title Dean of Women - the distinction Dean of the College for Women was not made, as we suggested, until 1930. So these men - since I put this idea before them - and women - Gertrude Herdle Moore was a member - accepted this.

There were no strained feelings on anybody's part at any time in this committee. It was a wonderful committee to work with. And we went on from there. And all kinds of names were put together. And I was the one who was supposed to do the background reading and I would bring in other names and tell what they had done. And finally one wintry day, I went to a meeting and I said, "I think I have it." And Dr. Slater listened very carefully, and when I explained it, he said, "You have it. That's it" which was a very pleasing response. The thought that had occurred to me - I was reading early in the history of the University, Lewis Henry Morgan was an early trustee of the University[28] but this was not his only interest in education. He was a trustee in 1850 - in the early 1850s - I don't know when he was first named but I know he was in 1853 when they went to the Prince Street Campus. But before that he had been so concerned about higher education for women that he, with several of his friends, called on people from house to house to gather funds for a College for Women to be built in Rochester at that time. And he very nearly gathered enough money. And Azariah Boody offered him the Prince Street Campus for this college for women.[29]

HB: Oh, how fascinating.

MA: Before he offered it to the University of Rochester. So you see, Lewis Henry Morgan had a very early hand in sponsoring the education of women. And when they failed by a small amount - they just couldn't get any more together and they accepted the fact that it was not possible at that time to establish a college for women, then Azariah Boody offered the Prince Street Campus to the University of Rochester, which accepted it, and that's where Azariah Boody and the University met. So Lewis Henry Morgan you see all the way through his life was interested and his - he and his wife[30] made a will and gave the bulk of their estate to the University at their death to be used for the further education of - higher education for women at the University of Rochester.[31] This was the very first large gift. And I said therefore I would like to build an arc in time - historically speaking - Lewis Henry Morgan carries that first thought. I would like to have one of the halls named after him.

And then later in that century there were - there was a group of women that sponsored education - higher education for women - and we - of course added Susan B. Anthony's name. There was no question about her contribution. So there were four halls, Susan B. Anthony's name was the second. And then, just about the turn of the century, Mrs. George C. Hollister's[32] name was cleared. She worked consistently with all the people who were working on the college - on education for women. And she had a very close connection with the University. Her husband, George C. Hollister, was a member of the University of Rochester Class of 1877. He was a trustee of the University from 1890 on. They were parents of twins, Mrs. Elliott Frost[33] whose husband was the first head of the Psychology Department, and Mrs. Thomas Spencer[34] whose husband had been a long-time trustee. So the associations with the University are very close in that family. Then Mrs. Gannett[35] was the - was the other major figure. Mrs. Gannett was someone whom I was privileged to know. During my college career, the City Club was very active and their Saturday noon meetings - and this was before television - they brought to the City of Rochester the top people in - in a wide range of subjects, to speak to the City Club meetings Saturday noon. Women were not members of the City Club but they were allowed to go to the balcony and listen to the talks. And Mrs. Gannett was a regular member there and I'll never forget her -her thick braids in a circle around her head. And the men welcomed her questions, which was an inevitable occurrence every time, a very penetrating question in a clear, matter-of-fact tone of voice--down from the balcony came the question from Mrs. Gannett. I - so that those people - those were the four people who were really significant in the development of the support for the education for women. And that was the suggestion that I made and that was what the Committee said we owned: "We've now concluded our search for that." And so those names were given to the Women's Residence Hall.

HB: This is fascinating. As you researched this, what other names cropped up?

MA: Well, let me tell you - they are listed and I think perhaps that's the best answer. They are listed and I think this should go into the record. The Rosenberger book, Rochester: The Making of a University[36] - he did a very careful thing there and it is crammed full of documents - documentary information. I think it's the one source that is good. You have to go to many sources to implement that. There really was no other really outstanding person who - it was a very loyal group. Oh, Mrs. - Mrs. Henry Danforth[37] was a real problem. Yes, this was a real problem to the Committee because Mrs. Danforth was, as a young thing, a member of that group before the turn of the century, and then did so much for the City and for the University. So again, modest and able and tremendous--a great person, there's no question about it. And we really were unhappy not to be able to give her name to a building. Bless her heart, she was in her nineties but she was still alive, and therefore we could not give her name. And we were very cute, I think. We said her name has got to go on the record, and we named the dining hall of the four halls the Danforth Dining Hall. So that that is still there, and I think everybody was happy that we solved that problem.

HB: So that among the women Susan B. Anthony and Mrs. Gannett and Mrs. Hollister - and Mrs. Danforth was a part of that group. Were there other women who were -?

MA: Yes, and they are mentioned here but - but there is no other major figure that - there were - you see the Women's Educational and Industrial Union[38] is a core of that kind of person that Rochester was very fortunate to have.

HB: Way ahead of their time.

MA: Way ahead of their time. So that I think you go to the group that formed the Women's Educational and Industrial Union for those names and those would be the same names.

HB: I have two extraneous questions. One was what resources did you use? Now, you've got the Rosenberger book, what other sources did you research?

MA: The Library - the Library, you see - there are the documents in the Library--the Annual Reports back - The archives are full of the history, you see, which is the way it should be. So that any specific part of the history I could go to.

HB: The minutes of the Board of Trustees reports of meetings?

MA: Right. And also - also - different memorial addresses. For instance, in 192-, I read in Rosenberger the other day - in 1925 the 75th - 1925 was the 75th anniversary of the founding of the University of Rochester and there was no great recognition, but Dr. Slater gave a talk in Kilbourn Hall on "The University at 75," which was later published. And that kind of book, you see, I would take out and go over very carefully. "The University at 75," you see, is very inclusive and it was a lengthy - for an address - I don't know if they amplified it for the book or not. But it - there are a number of things of that kind that the University has that are very rewarding to read.[39]

HB: Now, my other question is can you fill in a little more about Lewis Henry Morgan? His papers have been given to the University, I know.

MA: He was one of the first - I think he was the first internationally known anthropologist. In fact, he had a fame that some people are a little unhappy about because - are sensitive about really - it's humorous, I think really. Russia thought that he was one of the great men of the world and sent to the University of Rochester and wanted a copy of all of his writings. But he was internationally known and through his life he produced as an anthropologist. He was a scholar. And again, in this Rosenberger book it will tell you about additional things he would do civically for the City. So that he - he was - he was a very well rounded person. The reason I think - as I remember my reading – now this was sometime back - the reason that he was so eager to have the education for women made secure was the memory of his daughter. And I think she died of scarlet fever, something like that. And he was not only so saddened but he felt that he wanted to do something to do her honor. And so there is that personal element in it as well.[40]

HB: I recall as a student that his papers had to do with the family patterns of Indian tribes and -

MA: He specialized in that, yes. That's right.

HB: He spent a great deal of time in the Indian tribes of the Finger

Lakes region and -

MA: I can't remember now what Russia was so interested in it for.[41]

HB: Well, because the tribal - as I recall, the tribal patterns in cousin relationships and sibling relationships were quite similar with what some of the tribes in Russia were. And -

MA: So that was of interest to them. Right.

HB: They had scholars over here, I thought, who were -

MA: Oh, they did. They are very thorough--anything they do, they - they - they don't do lightly.

HB: Isn't that interesting. How long did it take you to research this, Marian?

MA: Well, you see, this was - well, I was working full time but this Committee went on for perhaps two years before the move, and two years after the move were regular meetings.

HB: Oh, my goodness, this was a full time job--the research.

MA: One of the things we did which no action was ever taken on. After we - perhaps the second year on the River Campus - was a study of University seals. And that took a great deal of time. I got copies of many of them to take to meetings to indicate how other institutions represented what - what they stood for. There was a feeling that the University's seal was flat and perhaps too simplified for the University that was in existence then. It didn't suggest the degree of research in science, for instance. And we spent a good number of meetings discussing this, but - and we made recommendations to the Administration, but nothing went through. So that nothing happened on that, but that again was a very legitimate subject for this Committee to take up. One thing -now here- here's a smaller thing, the University colors. We worked on this while we were still on the Prince Street Campus. If you ask ten people what the University colors were, you would not get an agreement. We felt that this was not right. We should have an agreement on what the University colors were, whether it was just blue or the gold and blue, or whatever. So that we - we actually - and Gertrude Herdle Moore was the Chairman of the sub-committee on that. And the final result of that was that - and this was accepted by the University, so this is official now. The gold - the dandelion yellow - the gold and blue, and the blue was carried out to the degree so we knew which blue it was by the Munsell System, the numerical thing - the number in the Munsell System which is a universally recognized system to show shades and hues, and so forth. So that the University colors were made official which is a good thing.

HB: Are there different kinds of seals, formal seals and workaday seals?

MA: No, no, there is one seal. There should be one seal for an institution.

HB: But I see some very elaborate things in some publications of the -

MA: The University?

HB: Yes, that aren’t just. Now this is the accepted -

MA: That is what was carried over -

HB: On my Commencement program sometimes I see more formalized elaborate seals. That's just an artist's view-

MA: I don't know. They may have taken action since then, you see. I mean, this may have been carried on and something may have been accepted. However, they wouldn’t be using two. I think they - I think that's not accepted officially - you see, two official seals.

HB: Now, Marian, in the course of this fascinating involvement with this Committee, what kind of personal things happened? You have alluded to some of them, Mr. Hutchison specially. Are there little warm humorous, human-interest stories that occurred?

MA: Well, I think of one that occurred before I was alive. But I - Dr. Slater told it on himself one time and with such humor that I’ve never forgotten it, when he was talking about the early days of the University. He came to the University in 1900[42] and in the 1900s, the very early 1900s there was no Eastman Theatre, no place for the Commencement ceremonies to be held that were adequate. And so they used the Third Presbyterian Church. And Dr. Slater told the story and he just chuckled all over. It was delightful just to watch him tell the story about the Commencement when he was Marshal, in a top hat with the Marshal's mace. He stood at the beginning of the procession in front of Anderson Hall. I can’t remember whether this particular - I know that some of the early ones they had a band, but I don't - I can't remember whether that occurred, at this time or not. But the faculty lined behind him and then the students followed, and he turned around and all was well, and so he started off in a stately gait across the circle and with great dignity and state, walked across and headed toward University Avenue, and after that amount of time, he turned around slightly to see what was happening, and nobody was following him. [Much laughter]. So he had a lot - this is a little suggestion of what they were up against in the early days too.

Also one thing that - that I think gives - has given meaning to the University that he did, was he was a great orator. His book on rhetoric was recognized by people teaching English for years and years and years and years as being unparalleled.[43] He was a scientist--his son was one of the ones who broke into the new science of today, and he knew about this E=MC2. In fact, one time when he was - during his retirement years, he took a course at six o'clock in the morning on television on some advanced science course. So that he was in a way one of our reasonable ideas of the Renaissance man. And he was a musician. And he wrote the Commencement Hymn early in the 1900s,[44] which for many, many years was sung. And it just - no one would suggest that it was great music but it was appropriate music for the occasion. And a thing that interested me, as I went to Commencement, which I always did because it was a moving climax to the whole activity of the University, was in those hundreds of people in the audience-they would hum along or even the numbers that would sing some of the words with it. They were responding to - and of recent years, the idea was brought up occasionally to drop it, and it was not dropped. But I think the last two or three years it has gone--it has not been part of it. I think that that is a loss.[45]

I think that another loss that we had built up in the normal natural way is that that academic institutions of vast learning have and keep the idea of a University orator. Now in many respects Dr. Slater was the University orator because given a memorial service, he would be the one who would be asked to give the address, and he would put into good English things that needed to be done. And again, President de Kiewiet recognized this as a valuable thing, and appointed Dr. Bernard Schilling as the University orator.[46] And he was very serious about this and very able, and he was interested in carrying on things that the great eastern institutions have, Princeton and Yale and Harvard of having things said in a beautiful way. He would - during the - for instance, the thing that - the thing that he would - regularly - Dr. Schilling would do regularly would be to write the - the - paragraph that would be used on Commencement for an honorary degree - in presenting an honorary degree- and he asked me to help him on that, and he - he gave me a number of recognitions which pleased me so much. But his method was to as soon as the people were known, and the University of course would know this weeks before - and months before that- he would send me those names and we would gather in the records department everything that that person had written, or that was written about that person, and come two weeks before Commencement, we would gather them in piles on two tables in the reference department, and Dr. Schilling would come in and for at least a week, during the exam time usually, immerse himself in that so that he would become a part of the thinking of that time or that person. And his phrases would often echo the phrases, at least the tempo - the nature of the person. And he felt this very keenly, that this was a contribution to a great University, and I think it was. That again has been lost in the magnitude of the activities today. So that here are two things that we had that I think are too bad that we have just dropped.

HB: You mean Dr. Schilling does not still -

MA: Well, he is now retired - but they have - they have - they have divided up the - the - honorary degrees among departments so that a person representing - which was done at the University for many years. So that the - the department responsible for suggesting that person would -

HB: But maybe there isn’t the eloquence, the -

MA: No, no, there couldn’t be, you see. There wasn’t that kind of investment of a scholar in the subject. And then he would read these over to me. He’d say, “I - you are my sounding board,” and it was a very interesting experience.

(Both people speak at the same time)

MA: It was not just a sudden thing--it was an investment of -

HB: Agony of -

MA: It was an investment of time and immersion--he would be completely involved in that.

HB: Isn’t that interesting.

MA: I think that’s interesting. And there again, I give credit to President de Kiewiet for catching the idea of elements of greatness of the University, and I think those are important. Dr. Rhees had that too, you see. He was an eloquent person. So that the University was blessed really with Dr. Rhees and Dr. Slater and Dr. Schilling-- we were really blessed.

HB: Marian, when you were a student did you go to classes on the far side of University Avenue in Catherine Strong Hall and -

MA: Yes, yes.

HB: Were there instances when you were over on Prince Street?

MA: Oh, many. Oh, many. Many of the classes were in Anderson Hall.

HB: Now how about chapel? As a senior, did Dr. Rhees give a course for seniors?

MA: Not at my time. Not at my time. No, Dr. Rhees didn’t turn up in chapel. He used to preside, I think, in chapel in earlier years in Anderson Hall.

HB: I see.

MA: But our - our chapel was required and we had to sit in a certain seat in Catherine Strong auditorium. And, bless her heart, Dean Munro - I give her credit for my learning as a good Presbyterian - learning the Episcopal prayer of Thanksgiving, and I enjoyed that. But otherwise people didn’t really take to it too much. Oh, there was one other thing. Dean Munro would make announcements, and one point that she made I have never forgotten. When she would tell about an organization that was going to have a certain thing and the fact that names should be signed on the bulletin board, she said, “Please do not say ‘sign up for.’ You do not sign up, you sign.” So that that was a thing that I enjoyed from Dean Munro. I’d like to say something about Dean Janet Clark.[47]

HB: Oh, please do.

MA: She was the - the person, of course, who blazed the trail was Dean Helen Bragdon who was the first Dean of the College for Women and came there in - when the women had the Campus - the responsibility of the Campus - there were men on it in 1930. Well, Dean Janet Clark was the second Dean and I think that she gave - I was very fond of her and I have great respect for her ability as a person and as a scientist. And she was recognized academically as an equal by the faculty, which I think is an accomplishment. And I think that was a little early too. And she came, of course, from a background--her father was Dean of the Medical School at Johns Hopkins[48] and she herself had been head of - of a fine Preparatory School.[49] But she - she was, I think, a fine person, and in a way she epitomized the excellence of - of women in the academic field.

She came at a time when the men had gone to the River Campus. The Men’s Faculty Club had moved to the River Campus from the dear little brown house under the pine trees on the Prince Street Campus. That was taken over by the new organization, the Women’s Faculty Club. And although it was run by the Women’s Faculty Club and the several bedrooms that were rented to women’s faculty there were filled by women that had been filled by men. The lunches were fascinating, and they were very well attended by men. The men said -the Men’s Faculty - the men on the faculty - you see there was one faculty. This was the very important thing that made it important, valuable; the University of Rochester College of Fine Arts had one faculty. Those people taught on both the Men’s Campus and the Women’s Campus, and it just simply depended upon which class they were teaching and where it happened to be whether or not they would be on the Prince Street Campus for lunch. And many of them tried to plan to be there because they said that it was much more informal and much more stimulating conversationally than it was in the Men’s Faculty Club where the people came in and sat by departments, and so the same old faces faced you at lunch. And the Women’s Faculty Club had two large oval tables that were very popular. Everybody - there was a cross representation there of all departments and all kinds of people. So that I think that was a contribution.

It was a very strong campus. We were not - we were not a weak sideshow in any respect. I think it was the only decision to make, to move to the River Campus, given the economics of the situation. I don’t think that there was money enough to continue and to enlarge and to make a strong college for women as well as a strong college for men, and do the graduate work that had been done. So that I - I think it was the right decision. I still believe, however, in the principle of college - colleges for women. And I think one of the beautiful illustrations is the five-college system in Massachusetts. I began my college career at Smith and have a great loyalty to Smith. It seems to me Smith has - has values of excellence that they never relaxed: the combination of excellence and the interest in the person. And when we had our 50th anniversary - reunion - there in 1975, 80% of our class came back to reunion.

HB: At Smith?

HA: At Smith. And gave - we gave $280,000 at that time - no large gift - this was - this was medium-sized gifts from many people. And the gifts kept coming in so that we were way above $300,000. Now the University here makes nothing like the investment in its alumnae, and when they have a campaign it is hard work. But this is one way that you - the result - you can’t help but contribute to a place that has meant so much to you continuously. Now, this is a little off the point. The point that I was really aiming for was the fact that several of the women’s colleges - colleges in the East - have voted on the question of accepting men students--becoming coeducational. And several years ago Smith voted on it and decided not to. And I think they have the best of both systems in their setup now because, with the five colleges in that geographical area - there is Smith and Mt. Holyoke and Amherst and the University of Massachusetts and Hampshire College - and any student at any one of those five institutions can take any course – they don’t have to give a reason for it. They can enroll in any course on any one of the other campuses. And the last three or four years they have worked out a bus system. And this takes a tremendous amount of - bugs - working out the bugs. A bus leaves every half hour to go from one campus to another, so that you have - you have the beauty there of the stimulation of a variety of people, and still you have the strengths of a college for women. I think that’s an ideal. But you cannot - you cannot set that up.

HB: But with a coordinate college - we did have this and - (both speak at once)

MA: As a coordinate college it was really good; there was no question about it.

HB: And the women had the opportunity to get a hands-on experience in administration and human relations that perhaps they don't have -

MA: I'd like to give one more little look back into the past which I think is of interest. When I was a senior in the College for Women, the League of Women Voters had been organized for two years, and that year, their second year, for the Annual Convention, they felt that the emphasis should be on the new voter. And as a senior, to represent the students of the College for Women, I went to that convention which was held at the University of Virginia - of Richmond, Virginia. And the excellence - again the excellence - they knew what they were doing - this has been consistent in that organization. They knew what they were doing--they knew how to preside. Their setups were by state, just as any Republican or Democratic convention is now. And thinking back to the leaders of women's education, I had a thrilling experience there because Carrie Chapman Catt was there. And she had a birthday[50] during the convention, and the New York State delegation had a birthday dinner for her, and they invited the students who were from the different colleges in New York State to attend. And I sat across from Carrie Chapman Catt. I didn't believe she was real. But she was perfectly delightful. And the suffragette angle was long gone, you see. You didn't get any strident thing and she had some delightful stories. And she was a great personality. She had many characteristics that Mrs. Gannett had, but more of a public speaker. I mean she could - she could - well, Mrs. Gannett could do that too but she was a great person. So that I had my introduction to the League of Women Voters early.

HB: What an exciting experience!

MA: And again, the University- the Women's College benefited by that, and it was all a part of that. I think maybe there is one little thing. If you want to wind this up, I have one little story.

HB: There's one -yes, I'd like to hear the story and then there is one thing I'd like to ask you. [Loud click is audible on the tape at this point.]

Marian, you've covered a broad span of reflections and recollections. At this point, could I ask you, from your broad experience as student at the University, as a Librarian at the College for Women, and later as a staff member of the Library, the Rhees Library, under the merged College, could you share any reflections that might indicate the great strengths we had as individual colleges of a great University, either to personal example or - of people you reflect on- or as experiences you've had that stayed with you that have been so meaningful in life?

MA: Well, the University in that respect really falls into three categories, as it should: the Arts College, and the Medical School, and the Eastman School of Music. I think the University was extremely fortunate, and I think perhaps we have a great deal to be indebted for that

to Dr. Rhees, because he could choose people. We had - and even before Dr. Rhees - we had really some giants in their fields. The Medical School had giants, and as I became adult and had several things happen to me, in my back and so on, I came in contact with the top people there, and recognized the fact that they were fine people, as well as scientists. Now that is true of the Medical School, it certainly was true of the Arts College and the Eastman School of Music had some superb people. They had Barbara Duncan[51] who was the organizer of the Library there--was an exceptional person. She made many buying trips to Europe[52] and was able to buy - again the timing was right--things were available then that are no longer available. But the Eastman School of Music Library is, I think, without question, the strongest academic school of music library in the country, and primarily for that reason. It was started with - again Dr. Rhees gave Miss Duncan every encouragement, and the money could go with it, and that was followed by Ruth Watanabe[53] who has been an exceptionally good librarian. Here's one other instance of Dr. Rhees's wisdom from my - as I saw it. The men the College for Men went into action in 1930. One of the things they needed was a Student Union. They built Todd Union, and very soon they realized that it was inadequate. So when the College for Women was being contemplated, it was recognized that the students would need a Union - a Student Union. And Dr. Rhees, bless his heart, said, "We're going to do right by the women. We're going to have one that is adequate." And he named three women who could travel and visit any institution that we heard of that would give us good ideas, and I was one of those three, very happily.

HB: Great.

MA: And every single place we visited we wrote up - got their suggestions. "Do be sure you don't forget this--we forgot this and it's important." And, "Don't do this--we're sorry we did it." We sent a complete report of that to Dr. Rhees, and every single point was followed.

HB: Oh, great. Who were the other two, do you recall?

MA: Helen Chattel - no, Ruth Chattel - and Mrs. Seward who was the Chairman.[54] And Mrs. Seward, bless her heart, said, "The men always travel in good style and we too are going to travel as the men have traveled." So that we traveled first class, by train, and stayed in the finest places. But there again, that was Dr. Rhees's reaction to a situation. The best was the right thing to go for. And it was accepted.

There's one little personal thing that impressed me. Dean Gale[55] was Dean of Men before the College for Men moved to the River Campus. And I had no connection with him at all, no reason to - I had no class with him and no reason to consult him. And soon after I graduated, when I was in the College for Women Library, I went over to Anderson Hall one day and went up to the second floor where the Deans' offices were, and started down the corridor, and he came out of his office, and instantly - he had not seen me in the distance and begun to say, you know, categorize what, you know, how do I know this person. Instantly he said, "Hello Marian." I couldn't understand it-I couldn't believe it. But you see he thought of - he was so concerned about each student--he made it his business to know each student. Now that is one instance where a small college has a tremendous advantage over a larger institution. There are many places in the classroom and farther out where that is evident, but I think that unless you have - well, a top administrator is a great help, if he is that kind of person who is interested in the individual, and can speak to the individual even in large meetings--it can be done. As he has that kind of concern for the person, it can come through. It can come through in discussing problems in a meeting; it can come through in his plans that he thinks about in his own office, by himself. I think it's the quality of the recognition of people, that can really change the whole quality again of an institution. And if you don't have it from the top, I think it has to be gained at - as the institutions become larger and larger and into the thousands - in the smaller units between a faculty and a student, or in a division head, and those are indeed fortunate occurrences. But one cannot have size and all of the values of a small organization simultaneously without something paying a price.

HB: Marian, you spent many years in Sibley Library, what happened to it when it was demolished?

MA: Oh, that was one of the few buildings that was taken down.[56] Anderson Hall still stands, bless its heart, and of course the Memorial Art Gallery is still there and expanded and is very strong. This is again - the Memorial Art Gallery as well as the Cutler Union were two very strong contributions to the vitality of the College for Women from 1930 to 1950. They were there on our Campus. Well, Sibley Hall had to go down. It was not - it was not feasible to have it used by any other organization or organizations. And I love to think of the fact that the stones that went into the building of Sibley Hall still live and have their own life in the Education Building of the Christ Episcopal Church in Pittsford. It's almost a complete match- a perfect match - with the stones that were used to build the Christ Church itself. It's a great success, and I 1ike to think of them as having another life.

HB: That's very interesting. What a fitting way to wind up our visit this morning. I want to thank you on behalf of the Friends of the University for being so willing to share these reminiscences and so much of the material you researched so carefully to become a part of our record, so that scholars of the future can enjoy some of the warmth and personal reflections that you have shared so graciously with us. Thank you very much, Marian. It has been a delight.

MA: Before we finish, Helen, I just want to say that you are an instance of one of the persons from the College for Women that made it so memorable, really. You are - you are one of the success students that - a beautiful illustration of -[57]

HB: Aren't you kind to say that. Thank you very much.

MA: I always thought that and I should say it in words for the record.

HB: Gracious, what an inspiration that will be for the rest of the month. Thank you so much, Marian.

[1] 80 Highland Ave, Rochester, NY

[2] The Committee on Sites and Traditions. “The Committee will be requested to consider the development of sites and the perpetuation of those traditions that have significance in establishing the proper silhouette of this University. The need for such a committee is made urgent by the forthcoming merger of the Arts Colleges on the River Campus.” 9.8.1953.

[3] Cornelis de Kiewiet served as University President form 1951-1961. Among his works are Anatomy of South African Misery (1956), British Colonial Policy and the South African Republics, 1848-1872 (1929), History of South Africa, Social and Economic (1941), and The Imperial Factor in South Africa: a Study in Politics and Economics (1937).

[4] The University moved to the Prince Street Campus in 1861.

[5] The University had been founded in 1850 and occupied the United States Hotel from 1850-1861, a total of eleven years.

[6] Azariah Boody was a University trustee from 1853-1865. He donated the land that became the core of the Prince Street campus.

[7] The merger took place in 1955.

[8] The University was founded in 1850, not 1853.

[9] The College for Men and the College for Women were set up in 1930, not 1950.

[10] Helen Bragdon is considered the second Dean of Women, serving from 1930-1938.

[11] Annette Munro was the first Dean of Women at the University serving from 1910-1930.

[12] There are some errors in the dates given in the previous few comments. The merger took place in 1955, not 1950. The Prince St. campus was occupied in 1861, not 1853.

[13] Sibley Hall was built in 1877.

[14] Sibley Hall was demolished in 1968.

[15] The statues are currently located in a garden between Rush Rhees Library and Meliora Hall. The six statues represent the realms of Science, Astronomy, Transportation, Navigation, Commerce and Geography.

[16] Mrs. Harper Sibley (Georgiana Farr) was the wife of UR trustee Harper Sibley. She was also president of the National Council of Church Women and an honorary alumna of the UR. They lived at 400 East Avenue, Rochester.

[17] Correct spelling the sculptor’s name is Ehrich, not Ehrlich.

[18] Dean Ruth A. Merrill was Director of Cutler Union and social advisor of the College for Women.

[19] The dandelion is now located on the façade of the Goergen Athletic Center.

[20] Sir Thomas Browne, [1646].

[21] Charles Hutchison, UR1898, began working for Kodak 1899 and “began a long, distinguished career as a close associate of George Eastman and controller of film and plate emulsion for the US and Canada. As an authority on the design of emulsion, Hutchison is recognized as the primary developer of the Kodak Park facilities for emulsion making. He retired in 1952 after over fifty years with the company.”

[22] Charles F. Hutchison was named a Trustee in 1932 and held the post until 1959 when he became an honorary Trustee. He was a UR Trustee for 42 years.

[23] The class tree markers are indeed preserved in the University Archive in Rush Rhees Library.

[24] The plaque reads “Oak from Stratford Class of 1864 Planted on the 300th Anniversary of Shakespeare’s Birth”. It was located a little west of Anderson Hall and was donated by the Ellwanger & Barry firm.

[25] Donald Bean Gilchrist [1892-1939] served as University Librarian for twenty years from 1919 until the time of his death in 1939.

[26] W. Allen Wallis served a UR President/Chancellor from 1962-1975.

[27] Clara Louise Andrews Hale.

[28] Lewis Henry Morgan was never a Trustee of the University, but was named an Honorary Graduate A.M. in 1851. He had served as the University’s attorney during the complicated and lengthy process of obtaining a Charter from the State Regents.

[29] This college for women was actually called the Barleywood Female University and Lewis Henry Morgan was the secretary of its Board of Trustees.

[30] Mary Elizabeth Steele Morgan.

[31] Included in Morgan’s bequest to the University were his extensive library and his papers. These materials are now held in the Rush Rhees Library’s Department of Rare Books and Special Collections.

[32] Emily Weed Hollister, formerly Emily Weed Barnes of Albany and a granddaughter of Thurlow Weed. She married George Hollister in 1886.

[33] Elizabeth Hollister Frost.

[34] Harriet Hollister Spencer.

[35] Mary Thorn [Lewis] Gannett was the wife of Rev. William Channing Gannett, Unitarian minister in Rochester from 1889 – 1908.

[36] Rosenberger, Jesse Leonard. Rochester: The Making of a University, with an introduction by Rush Rhees. 1927.

[37] Edwine Blake Danforth.

[38] “The Rochester Women’s Educational and Industrial Union was organized in 1893. It was a women’s club that had as its goal the promotion of women’s educational, industrial, and social advancement. It was one of Rochester’s most influential civic reform organizations throughout the Progressive Era.”

[39] Slater, John Rothwell. Rochester at Seventy-five; address before the Iota Chapter, Phi Beta Kappa, delivered in Kilbourn Hall, June 14, 1925. Rochester, NY 1925.

[40] Morgan had two daughters: Mary Elisabeth, born 1856 and Helen King born in 1860. While he was on an expedition to the west in 1862, he received a letter in Omaha, NE notifying him that his elder daughter was critically ill and urged him to return at once. According to his biographer Carl Resek this event was the “calamity of his life” as Morgan determined that by the time he reached Rochester, his daughter was either recovered or deceased, and that either way he could do nothing. As he later learned in Sioux City, both daughters had died of scarlet fever. According to Resek, Morgan wrote in his Journal “Thus ends my last expedition. I go home to my stricken and mourning wife, a miserable and destroyed man.”

[41] According to Morgan’s biographer Carl Resek in Lewis Henry Morgan, American Scholar, Morgan’s book “Ancient Society…came to be viewed as a Socialist classic. Soon after reading it, Karl Marx died at London, leaving instructions for Friedrich Engels to acquaint European Socialists with Morgan’s discoveries.” P. 160-161.

[42] Prof. Slater came to the University in 1905.

[43] Slater, John Rothwell. Freshman Rhetoric. Two editions: a) Boston: D.C. Heath & Co. 1913, and b) the revised edition of 1922 by the same publisher.

[44] “Commencement Hymn” and “On the Campus at Old Rochester” musical score is held at the Rochester Public Library dated 1907. Latin, with an English translation, of the Hymn.

[45] According to a search of Commencement programs, the Commencement Hymn was last sung in 1970.

[46] The post of University Orator was created inn 1954. “As University Orator, Dr. Schilling presents candidates for honorary degrees and prepares the formal citations.”

[47] Dean Janet Howell Clark was the third Dean of the College for Women, serving from 1938-1952. She was also a Professor in the Division of Biology.

[48] Janet Clark’s father was Dr. William H. Howell, Professor emeritus of physiology at Johns Hopkins University.

[49] Janet Clark had been head of the Bryn Mawr School in Baltimore, Maryland.

[50] Carrie Chapman Catt was born January 9, 1859.

[51] Barbara Duncan was the first Librarian of the Sibley Music Library at ESM. Recruited in 1922, she established Sibley’s rare book collection.

[52] The “buying trips” were expeditions to Europe with funds from Hiram W. Sibley to acquire rare books and manuscripts for the Music Library.

[53] Ruth Watanabe, UR52GE, succeeded Barbara Duncan at Librarian at ESM and served from 1947-1984.

[54] Mary L. Channel, UR1925 and Mrs. Rossiter L. Seward, the former Avadna G. Loomis, UR1913.

[55] Arthur Sullivan Gale, Professor of Mathematics.

[56] The old Sibley Library building was torn down in 1968.

[57] Helen Ancona Bergeson was a member of the Class of 1938.

Add new comment