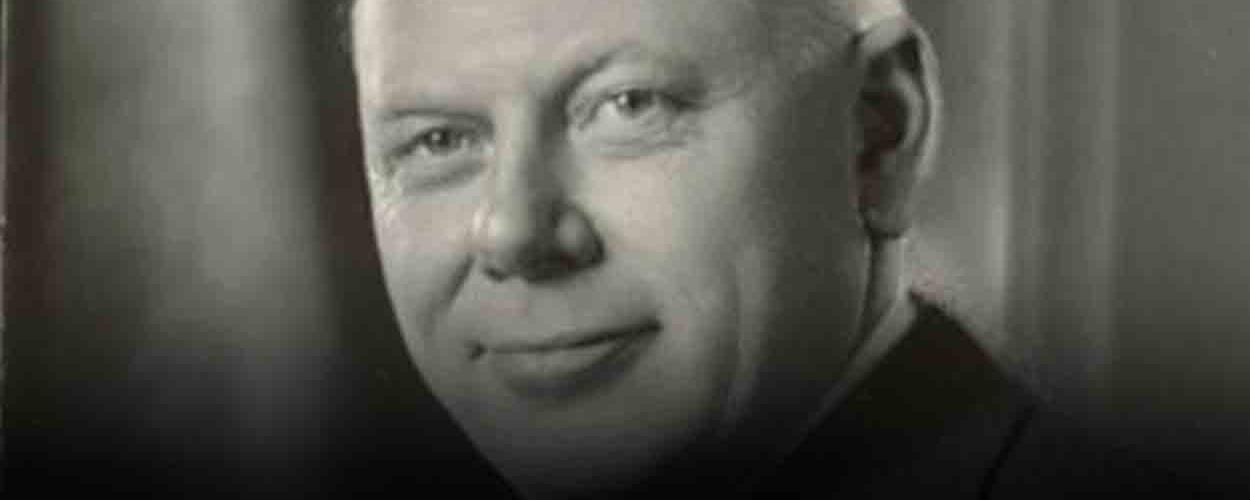

Dexter Perkins

Dexter Perkins

Dexter Perkins was graduated from Harvard in 1909 and earned his Ph.D. there in 1914, the same year that he was hired by the University of Rochester as an assistant professor of history. He advanced to full professor in 1925, when he became head of the history department. Widely regarded as an expert on the Monroe Doctrine, Perkins served as both president and secretary of the American Historical Association, and was the author of 17 books, many of them on the formation and conduct of America foreign policy. When he retired from the University in 1954, Perkins became the first John L. Senior Professor of American Civilization at Cornell University, a position he held until 1959. His memoirs, Yield of the Years, appeared in 1969. Perkins died in May, 1984 at the age of 94.

Please note:

The views expressed in the recordings and transcripts on this website are those of the speakers, and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, the University of Rochester.

All rights reserved. Copyright 2019.

JE: Uh, Dr. Perkins, what what prompted you to come to teach at the University of Rochester?

DP: Well, the answer is simple. My best friend in graduate work, who was also my classmate at Harvard, had come here in nineteen hundred and thirteen. And he agitated my appointment with Dr. Rhees and I had an offer in nineteen hundred and fifteen, and came here in the spring or the fall of nineteen hundred and fifteen. Largely it’s a matter of personal friendship. I was at that time at the University of Cincinnati.

JE: Mmm-hmm. Um, you once said that there’s a shortage of historians in the United States is this still true?

DP: Is what true?

JE: Uh, that there’s a shortage of historians –

DP: Today you mean?

JE: Yes.

DP: Well, uh – I don’t know what. . . There’s certainly a shortage of jobs for Ph.D.’s under the existing circumstances, I mean. The colleges – the appointments had been easy to get in previous years and they’re going to be much more difficult now.

JE: Mmm-hmm.

DP: Uh, I don’t know how history is actually holding up in universities but, um, there won’t be as many opportunities as there have been, probably.

JE: You also once said that, um, Russia is the key to our foreign policy problems. Is this still the case?

DP: I think it is, yes. I think – so the fundamental problems are of our relations with the Soviet Union and it’s very difficult to make a prognosis. But it does look, if you want to be cheerful about it, as if on both sides the economic costs of the arms race were getting to be so great that there may [at point?] be a greater possibility of understanding.

JE: Now would this sort of imply that there are chances for, um, world peace in the near future?

DP: It implies it very strongly to me. Uh, I’ve quoted very many times a phrase by Winston Churchill, “Peace may be the sturdy child of terror.”[1] We have a situation so utterly – well, the capacity for destruction is so great that the point of view there are going to be great precautions taken to avoid it. And we have now several concrete illustrations of that. There is for instance a hotline with Moscow, communication with Moscow in times of emergencies, quicker than ever before. They are now talking about an understanding with regard to a possible mistake and guarding against a mistake in the use of nuclear weapons. We already agreed to we are now engaged in talks – SALT,[2] they’re called – which look to limitation of the new defensive missiles, the –. I think, well, let me say one word more because this is the very heart of the things you want to talk about, the confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union in 1962 when they put missiles in Cuba. It was mainly caused by a direct challenge on the part of the United States. Uh, that taught both sides a lesson. It taught the Russians to be a little careful – that there were situations which they would find very embarrassing. It taught us to be careful because, although this is not so frequently mentioned, we decided we could put up with a regi – with a communist regime in Cuba if it wasn’t a danger to our security. And this is a great step forward on both sides.

JE: Well, um . . . what do you think the role of the President should be in the field of foreign affairs or are his present powers too great or too small or – ?

DP: Well, I think they should be very large, as a matter of fact, as they have been historically. I think the, it is the duty of the President now . . . to make his position clear. The technique will vary from time to time but, I don’t approve at all of these sudden decisions that President Nixon has recently made, without warning. I don’t think – I think a foreign policy in a democratic state has to be conducted by co – with consultation. That is not to say that nothing should be secret. It’s merely to say that they should be [signed for?] at any rate. To inform those who are also responsible.

JE: Mmm-hmm. Um, has protest against the Vietnam War altered the national policy to any great degree?

DP: Well, the Vietnam War – I think most of those of us who regard ourselves as specialists in the affair – in this matter would say that a war – our intervention in Vietnam was a mistake. Uh, a mistake that was, um, a mistake because the, a – what happened in Vietnam did not in any way directly, in my judgment, involve the national security. Now of course people have thought otherwise. But we not only we carried our – and it is only fair to say that every administration down to the Nixon Administration was engaged in enlarging our area of activity in Vietnam. But I think the historical view of the Vietnam affair will be that it is – it was an error. Now what’s going to happen now is a little different. Uh, I personally would favor a total withdrawal from Vietnam. But what is likely to happen, I think the political pressures diminish, as I think they have diminished, is that we withdraw all the ground troops in Vietnam but continue to give assistance to the existing government and possibly assistance in the air and certainly assistance in supplies.

JE: How do you feel about dissent in general?

DP: About what?

JE: About dissent in general.

DP: I feel that dissent is a very important part of the, uh – of the life of a democratic society. As a matter of fact I’ve written an article on this which has just appeared – I say “just,” within a year – in the Virginia Quarterly. Uh, in that I pointed out that dissent has existed in all wars and that it has never really seriously damaged the national interest. Uh, it’s, uh – I can think of no case where dissent has prevented victory, uh – by and of itself, and this war is the only war where it has really forced a change in the position of the government. We can’t live in a democratic society without expression of opinion.

JE: Now you were for many years an advisor to the State Department. Uh, what were your duties in that capacity, or to put it another way, upon what did you advise?

DP: Well, I – I can’t quite say that I was in the, uh – that I was close as, uh – as you imply to the State Department. I was a, uh – advisor on Latin American affairs in 1947 and I have been but I have had no other official connection to the State Department. I know many of the people and I’m from time to time informally I’m in communication with them. But I have not had any direct responsibility in the State Department at any time.

JE: I see. In regard to Latin America, why don’t we hear so much about the success of the communist movement there the way we did a few years ago?

DP: Well, no one of the states – you see, Cuba went communist over – almost a decade ago. And here we are now in nineteen hundred and seventy-one and no other state has followed this example. I don’t think communism is the right prescription. I think Latin America has recognized that it is not the right prescription. What has – what is already happening on the left in Latin America is something much more moderate. Uh, there’s a strong movement, as exhibited in Chile at the present time, for control of national resources, you know, where they’re taking the copper interests over. But totalitarian communism doesn’t look to be in the cards. Furthermore, the Latin American temperament is highly individualistic. Uh, it doesn’t suit the idea of a totalitarian state. They sometimes oscillate between dictatorship and disorder. Uh, but in general, communism is not, I think, what most Latin Americans believe in now.

In the process of your lecture tours you’ve traveled all over the world. Are the underdeveloped countries improving technologically or are they at a standstill?

DP: Well, it depends upon what you’re talking – what type of questions you – what countries you’re talking about. Uh, the problem for the undeveloped countries is a problem of how to attract capital and technology from the outside. And this is, now – some countries are so poor that they are bound to stagger along as they have in the past. You take a country like Chad, say, in Africa. There are no natural resources there to speak of. And it’s bound to be much the same as it was when it was a French colony. Country like Nigeria has great possibilities. And the question – the question as to how much development is going to take place will vary with the individual resources. We don’t pay enough attention to the natural resources as a basis of national prosperity. We seem to think it’s a matter of economic organization. It’s very much of a political organization. It’s very much a question of what you have to start with. And some countries are rich and some are poor.

JE: Uh, now to get to the University: of the many colleagues with whom you were associated while you were here, um, who impressed you the most?

DP: About the – uh, who impressed me – about my colleagues here or teach – ?

JE: [Um, uhm]

Well, I, of course a large part of my first twenty-four years here, were under Dr. Rhees. And I have him, I hold him in very particular esteem and affection. In those days it was possible to have an intimate relationship with the president. Of course, without the faintest criticism of the successor,[3] this has not been possible. And so in the academic sense of the term, Dr. Rhees is the man – in the administrative sense of the term, Dr. Rhees is a man for whom I have a greatest affection. In the professorial sense, I appointed many of the members of my department. Between nineteen hundred and twenty-five to nineteen hundred and fifty-three when I left to go to Cornell, we had a very united and harmonious department of which I was the head. Uh – Glyndon Van Deusen, Arthur J. May, whom everybody knows, Willson Coates, and other younger members, John Christopher. And these are the people of course for whom I have had the closest relationship. I think that probably – there are of course people outside my department of whom I was fond, but the man I was particularly devoted to for ten years at this institution was not an – a historian. He was Raymond Havens[4], who went to John Hopkins after long friendship with me, and whom I knew all the rest of his life, but that was a long time ago.

JE: Of all the, um, books you have written, this is probably a loaded question [laughs]--which do you think is the most important?

DP: Well, that’s not a bad question at all. Of course, . . . important is the word I have to think about. Undoubtedly my best-known book are my books on the Monroe Doctrine. And I suppose those are the ones that have had the widest influence. Sold really well, I mean, hundred thousand copies or something like that, is my general work on the Monroe Doctrine. But the books I’m attached to most are certain other ones. I think the essays I wrote when I went to Sweden in nineteen hundred and forty-nine and resulted in a book called An American Approach to Foreign Policy. And this I think is a much more original book than my research. And a little book I wrote on The American Way while I was at Cornell, which is just an examination of the character of American politics is a book I think which deserves more attention that it’s received. But those are the books I think of, I think, with particular affection.

JE: Of all the honors and awards bestowed upon you, which impressed you the most?

DP: Oh, beyond all question, my happiest day with regards – the – was one of – was the day I was elected to the Harvard Board of Overseers and at the same time received an honorary degree, a doctor of literature from Harvard. I don’t expect to top that. I have, I might say, seven honorary degrees, but of course the one that I hold also in affectionate memory is the honorary degree of the University of Rochester[5] which Professor Bernard Schilling made the citation which I put in my autobiography. But those – of course I have to go a little further because, of the things I’ve done that are extracurricular, my presence at the Salzburg Seminar, which was, which which lasted from 1940 – 1950 to 1961 has been my deepest satisfaction. But that’s another story, you probably don’t want to go into that detail.

JE: And finally, what do you think the future of the University of Rochester is going to be like?

DP: Well, that’s where, as I, uh – I remark many times whenever asked that kind of question. A historian always tells you about it after its happened –. [laughs] I should think it would be bright. I think there are problems ahead for all the universities, of course, as a matter of fact – but it seems to me that we have been moving along sound lines and that the reputation of the University has been growing. I see no reason to be otherwise than optimistic except as the whole story of education is going to be complex as time goes on. The difficulties that exist in American education today come from the enormous volume of students and faculty. And this is not a criticism of any individual institution but what is like – likely to be less of, what I think of sentimentally, is the close personal connection between the student and teacher that was possible when I came to Rochester. This again is a question of the situation, and not a comment on personalities.

JE: Thank you, Dr. Perkins.

[1] From his “Never Despair” speech (March 1, 1955): “Then it may well be said that we shall by a process of sublime irony have reached a stage in this story where safety will be the sturdy child of terror, and survival the twin brother of annihilation.”

[2] Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

[3] Alan Valentine

[4] Professor of English at UR from 1908 to 1925, then at John Hopkins from 1925 to 1947. Died 1954.

[5] 1956

Add new comment