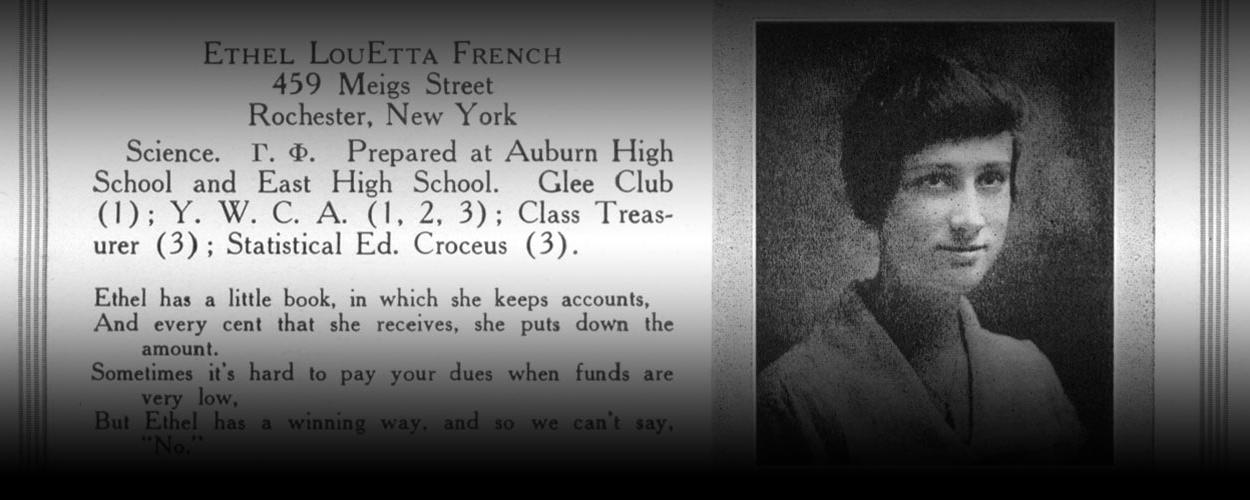

Ethel French

Ethel French

Dr. Ethel French, a professor of Chemistry at the University of Rochester from 1938 till 1977, was a member of the Class of 1920. She also earned her master’s degree in 1926 and her doctorate in Chemistry in 1937 from the University of Rochester. French grew up in Auburn, New York, and taught at Elmira College for three years before coming to Rochester. She served with four Deans of Women – Annette Munro, Dr. Helen D. Bragdon, Janet H. Clark and Margaret L. Habein.

Please note:

The views expressed in the recordings and transcripts on this website are those of the speakers, and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, the University of Rochester.

All rights reserved. Copyright 2019.

HB: This is a tape recording for the Friends of the University Libraries. I am visiting in the home of Dr. Ethel French, who was a student at the University of Rochester who graduated in 1920, received her Master’s in 1926, and her doctorate in 1937 from the University of Rochester. Dr. French, I want to thank you for being willing to share your reminiscences with us. It would be fun to talk about your student days first. Um, you prepared where to come to the University?

EF: Well, I was brought up in Auburn, New York and moved to Rochester for my senior year in East High[1]. From there I went to the University, and after graduating, I taught for three years at Elmira College[2], uh, which then, of course, was a college of about five hundred, and a college for girls. Uh, then I came back to Rochester to, uh, to be in the Chemistry Department where I remained for the rest of my teaching years, uh, and retired in about nineteen – either ’62 or ‘63, Professor Emeritus in Chemistry.

HB: So you've had a broad exposure to things happening at the University over these years. As a student, when you entered, um, what was the class like? Were there girls from just the Rochester area or were there students from other areas?

EF: I don't know how many girls entered, uh, in our freshman year, but we were—in 1920, er, 1916—we were not a very big class. And by the time we were juniors there were only about fifty-seven left in the class. And only three of those were out-of-state. The rest were all from small towns around Rochester. It was a very local situation.

HB: Um, when the girls came from small towns around Rochester, how — did they commute each day or did they live in Rochester or –?

EF: Uh, very few commuted. Uh, they would have board and room around somewhere near the campus, and then they would go home for weekends. That was one of the big disadvantages in those days that they didn't stay around for college functions as much as they should’ve. And we as a group didn't get to know each other as you do in dorms. In fact, when I lived in Elmira, I lived in junior – in the junior corridor and I had, uh, lots of opportunities to have college life and enjoy knowing the girls better than you did in Rochester in those days.

HB: Uh, what kinds of family background did the girls come from?

EF: Well, I don't – I would find that rather difficult, uh, to answer in that I didn't know them well enough, but, uh, many of their – I think some of their parents were farmers, small town business men, uh, others, Rochester. Eva Neun for example, she was from the box factory family[3]. Uh . . . I really . . . I don't know.

HB: But it was, uh, predominantly middle class around here?

EF: Oh yes, yes, predominantly middle class. Middle-class income.

HB: Yes.

EF: You know, none of us were wealthy. Well, we, uh, I think we only paid, uh, the tuition. We were – when I was in college it was three terms, and I think that the tuition was thirty dollars a term or ninety dollars a year.

HB: Fascinating. Now total three terms, that's interesting. Um, when did the terms run?

EF: Uh, they – one ended before Christmas, and – so that it was from May to June, I mean it was from fall to June, and it was divided into three periods[4]. Um, it was rather nice. Now, to give you some idea, it was only ninety dollars a year, but I worked all my — all summer after my freshman year in the Sibley Library inventorying books and I earned only ninety dollars. But I felt very great because I had earned my year's tuition[5].

HB: Paid your way through school.

EF: So it was – it's a relative matter sometimes.

HB: Very interesting. Now, as a student, did you have any preconceived ideas of what you wanted to study, or how were your courses determined?

EF: Well, I think you're really – it's a personal matter with me, I mean, Miss Hanna from East High very much wanted me to go in Chemistry, and I was interested, I knew, and so I really spent my time in college in the sciences, which from my point of view now is very wrong. I think you should have a more balanced program. Uh, Miss Munro[6] did her best to try to get me to have a balanced program but I, of course, wanted the science.

HB: How – what were your relationships with Dean Munro?

EF: Well, my personal relationships were abso – [coughs] excuse me, absolutely charming because I loved her. And, uh, I never was afraid of her – never scared, never thought of being. But many of the girls were simply petrified. When she'd send for them, they just quaked in their boots, and I don't think they had any need to because she was a lady – she was very much a lady and she was charming. She was very fair-minded. Uh, I know she was strict, uh, she had ideas of that time. In plays we were not allowed to wear trousers if you were taking a boy's part; you had to wear those terrible old black gym bloomers. And, uh, that was one of her rules. And we couldn't have – I think we could only have one college dance a year – we mustn't – couldn't have anything – any more than that. We always chaperoned her from her house over to the building and back again at every party. Uh, and she, uh, well, she believed in a gal being a lady and knowing enough to stand up when she came in the room and all the common courtesies, which I'm afraid today are slipping somewhat, and I think maybe she had a good deal to offer.

HB: So she was not only an academic dean but a dean of your student life?

EF: She was everything. Some people didn't feel that – well, she was always on the literary side and she emphasized that, of course.

HB: These are fascinating little gems about the kinds of rules she had. Do you think of other rules, uh, that the students abided by?

EF: Uh. . .

HB: They had one dance a week, were there others?

EF: Oh, one dance a year.

HB: One dance a year. Were there other social outlets for you?

EF: Well, we had things like college suppers, and, uh, poor Miss Munro, I remember her telling me that, um, she'd say, "Ethel, you know on the days when the girls have college suppers, I go to the Century Club[7] for lunch because I won't be able to eat very much at night." [laughs] And she was very generous with the Century Club. After I became faculty she, uh, invited us many times to the Century Club – the women faculty – to the Century Club and we always had a delightful time. Now I –

HB: Were there sororities at that time?

EF: Oh yes. We had sororities. There were, I believe, five sororities. And they were all very active[8]. And when I was a freshman, oh, people were really – uh, I didn't join a sorority until I was a junior, and then I joined Gamma Phi[9], uh, but there was great rivalry. Great. And of course we had our sorority dance once a year. Miss Munro would have nothing to do with that, you see. Uh, I think the place had to be approved, and we had to have chaperones. Other than that, I really –

HB: There were college suppers and sororities, uh, were there organizations related to study programs? Did you have drama groups or poetry groups?

EF: Oh, well, we had plays. We put on performances and then we always had May Day dance – you know, May Day and the May chains, and we usually put on a funny little dance or something like that. I can remember dressing up in white – white pantalets, or bloomers – to take the man's part in a dance.

HB: I think that’s charming – that's a beautiful reminiscence. Um, what were the, um, faculty like? Now you –

EF: Well, certainly I think I’m prejudiced. But when they talk today about getting outstanding faculty at the University and tell how remarkable they are, I wish they could have known some faculty back there.

HB: Let’s share some of your, um –

EF: Because I think people like Dr. Gale[10], um . . . Dr. Watkeys[11], Dr. Chambers[12], Dr. Slater[13], uh, were all in my day. And they, uh . . . they were real gentlemen.

HB: Did you have an opportunity to know them outside of the classroom?

EF: Not very much, no. I majored in chemistry and I was only – you see, uh, there were only two women, and I got to know Dr. Chambers very well and then stayed on of course, so I felt I knew him extremely well. Uh, Dr. Gale I felt quite close to. No, we didn't have very much opportunity.

HB: So that, uh, students going into the homes of faculty members or counselors, uh, student council –

EF: Oh, there wasn't very much of that, I don't think so, no.

HB: Uh, you said there were two women in chemistry?

EF: Well, there was – there was another gal majoring in chemistry but she left to go to Smith. And she was there two years, and then that year, Elsie Austin[14] decided to major in chemistry, so she took the other gal's place. So that there were really only two of us, as I remember, who, uh, majored in chemistry.

HB: Where did you have your classes? You probably had many classes in the Chemistry building on the Prince Street Campus?

EF: Well, we, uh, the Prince Street Campus was – I mean we were – it was open to us to go from Catherine Strong[15] and over to the Main Campus.

HB: You didn't have to study over at –

EF: Oh no, not in my day. No, those days had passed[16].

HB: Um, where did you have luncheon, or did you bring your lunch or what?

EF: Well, we had lunch downstairs in Catherine Strong. You could buy your lunch down there. There was a nice room over the, uh, in the gymnasium where we –

HB: Could men eat over there or just the women?

EF: No, just the women.

HB: I see.

EF: But it was – we went there for lunch for a long time, even after I was teaching there. That was in the days before the Faculty Club.

HB: When did the Faculty ClubHB: [17] start?

EF: Well, the Faculty Club – that started sometime about . . . I don't know – back in the early ‘20s, very early ‘20s because at first, you know, women faculty were not invited to participate. But, uh, a graduate assistant – a male graduate assistant – could go there for lunch but I, as an instructor, could not.

HB: Isn't that interesting.

EF: But, uh –

HB: This was in '23 then? 1923?

EF: Well, then I came back – '23, yes. In '23 I couldn't go there for lunch.

HB: Isn’t that amazing.

EF: But then, after a while, they became financially embarrassed and were very happy to have the women come in and from then on, it, uh, grew and really was a wonderful place to go for lunch because you met all the faculty and you had, uh, communication with other departments, you know, and it was really very fine.

HB: Everyone I've talked to says there’s never been the charm and intimacy of the Faculty Club as there was in that little old spot.

EF: In that darling little house that's now down.

HB: Those two big tables where everyone mingled, was just a melting pot of the whole thing.

EF: It really was very, very nice.

HB: Isn't that great.

EF: So often I would not be able to go over for lunch ‘cause I had labs every afternoon at one o'clock, and I would have to get things out for lab, but it really was a lovely spot. And the, uh, the woman who ran it added a great deal to it.

HB: Who was that?

EF: I can't remember her name. She lived quite nearby.

HB: We had wonderful strawberry pie, I remember. Oh, wasn’t that gorgeous?

EF: Yes, I remember the strawberry pie was marvelous, marvelous! And we had wonderful parties there, and we could entertain there, you know, ourselves, and have evening dinners if we wished to. We would prepare them ourselves but we – you could entertain, and it was a lovely place to entertain.

HB: Did Dean Munro live in that Faculty Club?

EF: No, no.

HB: Where did she live?

EF: Well, she lived with the Hales next door – next door to Catherine Strong. She lived all her time with the Hales[18].

HB: I see. Well, uh, for just a moment, let's hark back to your student days. The War was going on?

EF: Oh, yes.

HB: What was – what did that – what was the impact of World War I on student life?

EF: Well, you see I graduated in 1920 so we got . . . really the, uh, the whole effect of the War. 1918, you see, we were juniors, and that year we had the flu, we had a coal shortage, and I can remember – I'm almost positive college was closed six weeks – and maybe it saved a lot of lives too because we didn't get the flu in Rochester as badly as they got it many places like Philadelphia. So I can remember being home – and the only really [sic] I can remember is going up Monroe Avenue from little store to little store and getting a quarter of a pound of brown sugar in each store until I got enough for whatever purpose I wanted it. [laughs] And then, uh, we in Qualitative Chemistry that year, we lost six weeks of lab. Dr. Chambers had assigned the lab experiments for the year. When we got back we found he meant us to do them just the same. So many of us worked the next summer in the lab to complete the lab work. We resented that quite a bit. We felt that was very unfair. And I'm sure today no student would stand for it. Uh, their attitude has changed a great deal. In those days we believed we had to do whatever we were told to do. And so, we did it.

HB: When you, uh, were such a minority among science students, chemistry students, did you feel any differentiation from the faculty or the staff?

EF: Oh, you mean did they treat me differently than, uh, because I was a woman? Oh, I don't think so, no. I always felt that I was part of the staff, part of the department or – and very much a part of the department. I was – well, I worked with men like Bill Line[19], you know, Ralph Helmkamp[20]. Dr. Chambers, uh –

HB: They were real gentlemen, all of them. . . Um, you – the class of ‘18 was decimated; there weren't many men around in that class, were there?

EF: Well, uh, the men kept going, uh, the faculty kept going to war.

HB: There weren't many men students around.

EF: Well, of course, we had fewer and fewer men students, and, uh, men faculty. I can remember starting out in a course and the faculty went to war so then I took – started another course. He went to war so I ended in American history course for the rest of the year and learned nothing. We never got beyond the – I don't think we got to the – even to the Revolution. [laughs] Poor Miss Munro was – thought the Class of '20 was pretty bad. She – you know – the Class of '20 neither – no man or woman got a Phi Beta Kappa key.

HB: Is that right.

EF: We had the distinction of being the only class that has never had a Phi Bate. Well, really, I don't think it was all our fault. We were upset all the time we were in college, or nearly all the time, you know. Uh, and always coming and going –

HB: There wasn’t even continuity on the staff to make recommendations.

EF: And, well, yes, and, uh, I can look at some of these people now and I can certainly assure you that, uh, Ethel Gordon[21], for example, was certainly Phi Bate material. But . . . I really think part of it was because we were – our minds weren't always on it. Esther Horn[22], for example, was certainly Phi Bate, if there ever was anybody Phi Bate, she was – well, she wasn't, but I mean she would have been, I think.

HB: Was she a math student?

EF: She was a math major and really a brilliant girl. Uh, and I think Miss Munro might be quite surprised if she could come back now and see some of the successes in that class. I don't . . . I mean we had people like Doris Andrews Ogden. Of course I know she has raised five girls[23]. We had Dottie Trimby[24] and, uh . . . Arline Bradshaw[25]. Minnie Cleaver[26] was a smart little gal. So it goes. No, I think that, uh, we were rather representative of the average college student.

HB: Now it would have been in the University now for twenty years when you graduated – sixteen when you came aboard as a freshman – women were admitted in 1900 and then Dean Munro came in 1910. Were there still pressures?

EF: Oh yes.

HB: What kinds of pressures did the women feel?

EF: Well, uh, the big fraternities – the men – didn't speak to us in class. The – they really practically ignored us in classes. It never bothered me too much. The smaller fraternities didn't pay any attention to it. And many of the girls had a very nice time. Uh, they gradually broke the barrier and they would be invited to fraternity dances and college dances, so.

HB: Is it fair to say, then, the presence of the women on the campus was tolerated, possibly not encouraged?

EF: Oh yes, Dr. Rhees never wanted us, you know[27]. No, there's no question about that. I think that's, uh, public knowledge. He, uh, told Susan B. Anthony that if she raised the fifty thousand, that they would be admitted, but he never dreamed she could raise it[28]. And he never really, uh, he never really got used to it. And I think when the opportunity to divide the campuses came, I think he jumped at it. Personally, I think he jumped wrong to go up to Oak Hill. It was only eighty acres, and he wasn't farsighted enough to see that that very soon would not be enough land. But a group of business men in Rochester who owned Oak Hill, they would like to get rid of it and go out East Avenue[29]. So they sold the idea to Dr. Rhees and he unfortunately picked it up[30].

HB: I didn't know that.

EF: Oh sure. They, uh, he, uh . . . and look at the place they got out East Avenue. We could just as well have had it. If he had been farsighted enough to see that he was having something put over on him.

HB: Who owned that property out East Avenue?

EF: I haven't the slightest idea[31].

HB: What little group of business men were involved in –

EF: Well, the golf – the people who owned the golf club.

HB: I see.

EF: That's something I would have been told by – I’ve been told on fairly good authority that that happened.

HB: How about that. Um, let's jump for a moment back to your student days. You had a very clear vision of what you wanted to do. You wanted to get into Chemistry. What kinds of options were available to you in –

EF: We didn't have too many because really what were you going to do when you got through except teach? Uh, you could go from college to secretarial school and become a secretary. Uh, and, really, there weren't too many opportunities open. You could – if you wanted to be a nurse you would not bother to go to college in those days but they soon had the five-year course and then you went to college to be – and went, um, years and became a nurse[32]. But really not too many professions were open . . . to them. I suppose nearly every girl in this class probably taught school.

HB: So that teaching school, becoming a nurse – you wouldn’t go to school – or becoming married were the options that were open to women of your generation.

EF: Yes, and of course, uh, some of the girls lost their, uh, men friends in the War. As I really think most of them went into teaching. Many of them married. As I glance at this, many married.

HB: Um, what was it like at Elmira? You say you enjoyed student contacts in a way that you were not able to enjoy at Rochester because of the dormitory situation.

EF: Well, they had much more sociability. They had a very, very wonderful, uh, drama class. They put on marvelous plays. And they had weekly entertainments because they lived in the dorm and they were a unit unto themselves. And you did get to know people very much better. It was – and then in those days, they were very strict there too. Uh, a girl could not go out with a man for dinner at night unless a faculty went with them.

HB: Isn't that interesting.

EF: And so if you were young faculty, just out of college, you, uh, you became quite an important person because you could be a chaperone.

HB: Isn't that beautiful.

EF: And so, uh, I became just about a member of the junior class. [laughs]

HB: Much in demand. That must have been quite a burden on the young gentleman who managed to –

EF: It was sort of – I would say it was hard on them but, um, it was enjoyed by all. [laughs]

HB: Well, I was thinking financially, you take three out for dinner instead of two.

EF: Well, take three instead of two! Of course in those days it didn’t cost so much, but then, in those days we didn’t get so much.

HB: Didn't have so much money, that's right. That's lovely.

EF: And they couldn't – they had to have all their dances chaperoned, whether they had them at the college or out in town. And so I would say, “Well, you just find a man for me and I’ll chaperone you.”

HB: Oh, that's lovely.

EF: And I always – when the boys – we got lots of the men from Cornell, you know. And I would — they would say, "What year are you?" And I'd say, "Oh, this is my freshman – this is my first year – my first year." Or, "It’s my second year.” They never dreamed I – that was another secret the girls always kept – they never let on that I was faculty.

HB: Oh, that’s beautiful.

EF: So we had a nice time.

HB: So you came back, uh, into the Chemistry Department to get you master's degree? Um, did you have any special problem or were you taking additional courses or what was the focus of your study in chemistry, working for a master's degree?

EF: Well, in those days they sort of thought you ought to have a master's before you went out for your doctorate. But, uh . . . I went on in organic.

HB: I see.

EF: But I liked teaching inorganic better so that eventually I taught nothing but inorganic. Uh, the ordinary chemistry, beginning chemistry, qualitative and quantitative, uh, analysis, was where I –

HB: And as a graduate student were you doing teaching?

EF: Oh yes. You assisted in the lab, you, uh, every lecture occurred that Dr. Chambers had a headache, he’d call me at a quarter of eight in the morning and the class would be at eight o'clock and could I take it. And I'd say, “Where did you leave off?” And I would run from my own quarter and go puffing into class at ten after eight and start talking.

HB: Isn't that interesting.

EF: I don’t, uh, it was sort of hard sometimes.

HB: Was his health fragile or was this –

EF: No, but he would get these perfectly awful headaches, but he never seemed to call me until late, you know.

HB: Probably hoping it would go away.

EF: Well, that didn't happen, I suppose, too often. But it seemed often enough to me.

HB: Now you, um, concentrated in organic chemistry –

EF: I got my degree in organic chemistry.

HB: And you did much of your teaching in inorganic chemistry?

EF: Yes, I preferred it.

HB: What were the students like when you first started teaching? This would have been in the mid-twenties, wouldn't it?

EF: Well, in – well, I assisted in the lab here in the latter – before I left Rochester.

HB: I see.

EF: They were marvelous kids. And Elmira, of course, was wonderful. They – and so were the students when I came back. There was never any problem, you know, discipline or anything like that, with the college gir – with college men or women. I taught women at first – a great many women, you see, on Prince Street Campus. Some – and then when we divided, why, some men would still come back. But then when I went to the River, it changed. I taught practically all men and very few women. So I had, um, men . . . uh, I think men are more – well, they like science a little better as a rule. So that, um, they were – maybe easier to teach. But they were not as sincere, not as – wouldn't work as hard as women.

HB: Um, you observed kindly – kind of the gradual, um, dissolving away of the barriers for women in science. Now you were in a pioneer situation, kind of – one of two in the Chemistry Department when you were a student.

EF: Well, you see when – you see, women were in great demand in '20 because of the War. So that we were able to, uh, enter situations that we normally wouldn't enter.

HB: So that would have been denied you had there not been the need for having women in chemical positions?

EF: Mmm-hmm.

HB: As the numbers increased among women, did the opportunities for employment increase in conjunction with that?

EF: Oh yes. Yes, and I think that the, uh, trend has changed a little bit in the last – women became more and more important in the University and we reached a peak. And now I feel that women in the University are not as important and that they very often are replaced by men.

HB: It's an interesting trend. When did you observe in the build-up to the peak – under whose deanship was that?

EF: Oh, I really can't tell you.

HB: You served under Dean Munro, Dean BragdonHB: [33], Dean ClarkHB: [34] and Dean HabeinHB: [35]. Were there, um, certain characteristics of their administrations that personified them, or certain things stand out about them that were unique as to what their hopes for women's education might be?

EF: Well, I think that they were all very, very sincere in their desire to promote women. And, uh, I think that, uh . . . well, Dean Clark, for example, was very, very, uh, sincere in her desire to see the Women's College stay on the Prince Street and become a real Women's College. She was overruled and so we went to the River in '50 or somewhere around there.

HB: '50 or '52, something like that.

EF: We – '54, I think was – no. Wasn't it, uh, I think '54 was the last year that we were on Prince Street[36].

HB: I see. Mmm-hmm.

EF: And then we went to the River. Well, I think in looking back, I think it’s – I think probably it was a very good idea for the colleges to be combined on the River. I have always felt that it was a shame to waste this campus, and that this should have been made a junior college or else had the freshman year down here. Junior – it would have been very simple to have had a community college. The buildings were all ready. Instead of selling the chemistry building, which was cut stone and a beautiful building, to Cartwright who tore it down. And the dorms were there; we had plenty of space. It seemed too bad not to make something educational out of it, with Cutler Union[37], a beautiful building, probably the most beautiful they've ever built anywhere. And so it seemed to me it should have been for education.

HB: What do you think, um, the women gained by going over to the River Campus?

EF: Well, it was a – they gained being with the men all the time. Whether it changed their – did it change their educational outlook?

HB: Do you think it did?

EF: Well, I think that many a gal came there to find a husband; I don't think there's any doubt about that. Because I was girls' adviser, you know, I was adviser to both men and women over a number of years and some of the remarks of the young girls were interesting. "Why do you want to be a nurse?" I used to ask them. And their faces would look a little queer and she'd say, “Well, I'd like to marry a doctor." On the other hand, I think they were very serious, most of them. Are we as serious in education today or not? I don't know. People up there think they are. I think that their education has gone downhill. I don't think that we are putting – I think we’re putting out people, and we're putting out bright people. But when they say that they are brighter than they used to be, I don't know as I want to agree with them. They have more Phi Beta Kappas now. Yes, why? They've lowered their standard. Their educational standard isn't as high today as it was years ago, I don't think. Of course this could be – you know – I could be prejudiced but I don't think so.

HB: But you have observed it over a span that has given you lots of areas for comparison, through four Presidents and four Deans.

EF: Well –

HB: A lot of perspective.

EF: I used to be on the Admissions Committee and Isabel Wallace[38] tried very hard every year for years to get two Ne – black girls in the class, and she would probably get just one who would meet our standards. And you know that one didn't hardly ever stay with us. So how can we be admitting that number of blacks now without lowering our standard? We're lowering them. How can you do it – they haven't changed that much in a few years.

HB: You don't think education – their preparatory education – has improved?

EF: Well, it may have improved, but it certainly – it certainly isn't of the quality it should be. Not in the numbers. Now there are very bright Negroes – I'm not speaking against them at all. I think they're bright and I think they should be given the opportunity. But I feel resentful that we are now bending our backs to take care of those that really don't qualify. And you're just putting . . . I don't think that, uh –

HB: You feel that standards have lowered in general?

EF: Sure, I certainly do.

HB: Lower denominator.

EF: Mmm-hmm. Yeah.

HB: Do you think of any, uh, human interest stories or, um, things that occur to you about faculty or student members that you recall over the years?

EF: I know there are lots of interesting ones if I can just remember them.

HB: Dr. French, I want to thank you on behalf of the Friends of the University Libraries for sharing so many delightful reminiscences with us. I hope we may have another opportunity to visit, and perhaps more things will come to mind which you will be willing to share. Thank you. It has been a delightful day.

[recording ends]

Transcript by Eileen L. Fay (February 2014)

[1] East High School opened in 1902 at 410 Alexander Street. It was designed by J. Foster Warner, a famous Rochester architect. It moved to its current location on East Main Street in 1959. The original building is now the East Court apartments owned by Conifer, LLC.

[2] Elmira College accepted its first class in 1855. It is the oldest college still in existence to grant degrees to women that were equal to those given to men. It became coeducational in 1969.

[3] Eva Marie Neun, Class of 1920. Her father Henry T. Neun is identified as a “paper box manufacturer, florist” on her college application.

[4] According to the 1916-17 General Catalogue, the 1916 academic year began with Autumn Term on September 21 with final exams on December 22, 1916. Winter Term ran from January 3 to final exams ending March 28, 1917. Spring Term began April 5 and concluded with commencement on June 20, 1917.

[5] $90 dollars is indeed the correct tuition for the 1916-17 academic year. Students also had to pay an incidental fee for janitorial services and utilities, totaling $21 per year, as well as laboratory expenses ranging from $2-10. There was additionally a graduation fee of $10 required of all seniors. By the 1919-20 academic year, however, tuition had risen to $100 per year, plus $30 in general fees, to be paid in two installments. (source: General Catalogues)

[6] Annette G. Munro served as Dean of Women from 1910 to 1930. Like Rhees, she did not believe in coeducation but supported equal educational opportunity for women. She was a graduate of Wellesley College.

[7] The Century Club is a private women’s social club founded in 1910. It is still in existence in its original home at 566 East Avenue.

[8] The original sororities at the University of Rochester were founded as local social groups for female students, especially before 1930, when they shared the male-dominated Prince Street Campus. These sororities were at their peak between 1930 and 1955, when men and women attended school separately on the Prince Street and River Campuses. After the merger of 1955, when the Prince Street Campus closed for good, the local sororities declined until all had disbanded by 1970. National sororities came to the University beginning in 1978.

[9] A Gamma Phi scrapbook covering 1960-64 is available in the University Archives.

[10] Dr. Arthur S. Gale was a professor of mathematics who came to the University of Rochester in 1905. He was also the first Dean of Freshmen and pioneered the tradition of freshman orientation. He was later the Dean of the College for Men. The women’s yearbook, Croceus, named him “Man of the Year” in 1931.

[11] Dr. Charles W. Watkeys was a member of the Class of 1901. He returned to UR in 1908 as a math professor. He retired in 1946. He married one of his students (Ollie Antoinette Braggins, Class of 1908, who worked for a time as an assistant in the Mathematics Department) and was involved in curricular reforms.

[12] Dr. Victor J. Chambers was Class of 1895. In 1908 he succeeded Professor Lattimore as the chair of the Chemistry Department and remained there for three decades. He also served as Dean of Graduate Studies for six years. The Chambers House residence hall (1969) on the River Campus is named for him.

[13] Dr. John Rothwell Slater was a popular English professor who came to UR in 1905 and became head of the department in 1908, a post he held until his 1942 retirement. He also wrote the inscriptions found throughout Rush Rhees Library and played the chimes in the tower (predecessor to the carillon). His papers are available in Special Collections.

[14] Elsie May Austin, Class of 1920. She worked as an assistant in the Chemistry Department from 1920-22.

[15] Both Catherine Strong and Susan B. Anthony Memorial Halls were built in 1913 exclusively for the women students. They were linked by an underground passageway disdainfully called the “chicken run” by male students. Strong contained classrooms, a stage, a small library, administrative offices, and a lunchroom, while Anthony was a gymnasium.

[16] When female students were first admitted in 1900, a small, drab room in the corner of Anderson Hall was set aside for the women to eat, study, and socialize. It was equipped with a few chairs and nondescript pictures.

[17] The Faculty Club was formed in 1924 with Donald W. Gilbert as President. They leased a cottage from the University on the western edge of the campus to serve as a lunchroom, social gathering place, and living quarters for bachelor faculty. The Women’s Faculty Club took over the building after the River Campus opened in 1930 and the main Faculty Club moved there. Men were still welcome at lunchtime, however.

[18] May be referring to the family of Ezra Andrews Hale, Class of 1916. He has also done an Oral History interview.

[19] Dr. Willard R. Line was a member of the Class of 1912 who returned to UR as a chemistry instructor in 1914. He received an award for outstanding faculty service from the College for Men in 1948. He retired as professor emeritus in 1955 and had a scholarship for chemistry students established in his honor in 1966.

[20] Dr. Ralph W. Helmkamp was a member of the Class of 1911. He joined the UR faculty as a chemistry instructor in 1925 and served as President of the Rochester chapters of the American Chemical Society and Sigma Xi. He retired in 1958.

[21] Ethel May Gordon, Class of 1920.

[22] Esther Amelia Horn, Class of 1920.

[23] Doris Elizabeth Andrew, Class of 1920. She married Edward Mikels Ogden, Class of 1918. Their daughters were Doris, Katherine, Helen, Polly, and Virginia.

[24] Emily Anna Otto, Class of 1920. She married Milton Henry Trimby.

[25] Arline Louise Bradshaw, Class of 1920. She married John Russell Crockett.

[26] Minnie Alberta Cleaver, Class of 1920.

[27] From Arthur May’s History of the University of Rochester (1968):

Concerning collegiate education for women Rhees entertained strong opinions, albeit tinctured by elements of flexibility and opportunism. It was often accounted a handicap that in the presence of the other half of society he was habitually reticent and shy. Deep down the President favored a coordinate college on the general pattern of Radcliffe at Harvard, say, or Barnard at Columbia; even more desirable from his angle of vision would be a more or less independent, a distinct college for women. In point of fact his administration saw the application of both of these formulae, but the separation of the undergraduate men and women ceased a generation after he retired from the academic stage. . . Yet, since women had "distinct and in some particulars quite different interests, aims, and traditions," he welcomed signs of collegiate separatism. Ideally, the U. of R., he thought, should recognize that two categories of students existed and they should have "coordinate rights" with comparable facilities.

[28] In 1898 the Board of Trustees informed Susan B. Anthony that women would be admitted if she could raise $100,000. When Anthony and her allies were only able to come up with $29,000, the trustees agreed to lower the required sum to $50,000. When the final $2,000 proved elusive, Anthony famously offered her life insurance policy. Additional funds did come in, however, and the policy was returned to her.

[29] Oak Hill Country Club is now located at 145 Kilbourn Avenue, off East Avenue in the suburb of Pittsford.

[30] According to Sal Maiorana’s Oak Hill Country Club, 1901-2001: A Centennial Anniversary, the idea to build on the Oak Hill site was first proposed to President Rhees by George W. Todd, a local architect who was aware that both Rhees and George Eastman were interested in expanding the University. The members of Oak Hill initially met the proposal with “great skepticism” and negotiations were tough. “The members of Oak Hill loved their club, loved their location, and many had built more than 20 years of memories along the riverside,” says Maiorana. But they “recognized a golden opportunity that would ultimately benefit Oak Hill, the university, and the city.” There is also apparently an apocryphal tale, related in Once Upon a Time at Oak Hill by Bruce Koch (1995), that George Eastman was on a recreational flight when he looked down, saw Oak Hill’s riverside site, and exclaimed, “My, what a wonderful spot that would be for a new campus for my beloved University of Rochester!”

[31] The owner of the tract does not seem to have been recorded, although it had been used as farmland for over a century and was subsequently barren and decimated when Oak Hill first moved there. (source: Maiorana)

[32] The School of Nursing (SON) opened concurrently with the University of Rochester Medical Center in 1925. At the time, post-secondary training for nurses was a new idea, and UR was one of only a handful of colleges and universities nationwide involved in nurse education. SON’s innovative five-year program led to a Bachelor of Science with a major in nursing, going well beyond the recommendations in the influential “Nursing and Nursing Education in the United States” report by the Committee for the Study of Nursing Education (1923). The nursing diploma itself took only two years but the students were also required to take three years of liberal arts classes. (source: http://www.son.rochester.edu/assets/pdf/history.pdf)

[33] Dr. Helen D. Bragdon succeeded Annette Munro as Dean of Women in 1930. She had a doctorate from Harvard. She resigned in 1938 over irreconcilable differences with President Valentine over the character of higher education for women (he felt that purely intellectual interests should be stressed at the expense of extracurricular activities; she disagreed).

[34] Dr. Janet H. Clark was the successor of Dr. Helen D. Bragdon, who succeeded Munro as Dean of Women. Clark served from 1938 until her retirement in 1952. She had a doctorate in physics and held a professorship in the biological sciences. During her tenure as dean, she established a separate faculty for the College for Women.

[35] Margaret L. Habein came to the University as Dean of Women in 1952. In 1954 she was appointed first Dean of Instruction and Student Services. She resigned in 1957.

[36] The merger of the College for Men and Women was carried out in 1955.

[37] Cutler Union was completed in 1932 on the former site of the Alumni Gymnasium, which was razed. The male students had moved to the new River Campus two years previous, so Cutler was constructed to anchor the now-separate College for Women. It was named for the late James G. Cutler of Cutler Mail Chute fame (the company papers are available in Special Collections), who had financed the building’s construction. The Gothic academic tower was designed to suit Mr. Cutler’s tastes and was made of Indiana limestone. Ezra Winter was the architect. When completed, Cutler Union contained an auditorium, small meeting and reception rooms, classrooms, a chapel (named for Kay Duffield, a longtime religious worker on campus), and a cafeteria. It still stands today as part of the Memorial Art Gallery. The Van Brul Pavilion, an enclosed sculpture garden, was built in 1968 to connect the two.

[38] Dr. Isabel K. Wallace was a member of the Class of 1916. She returned to the University in 1929 and worked as a vocational counselor and placement officer for women until her retirement in 1960. She was a member of the local NAACP chapter.

Add new comment